– contributed by Tony Pankuch. For a screen reader compatible pdf of this post and documents contained within, click here.

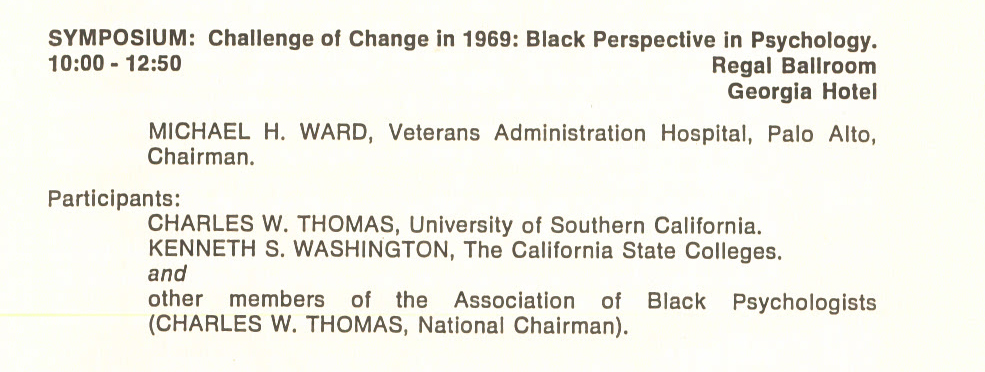

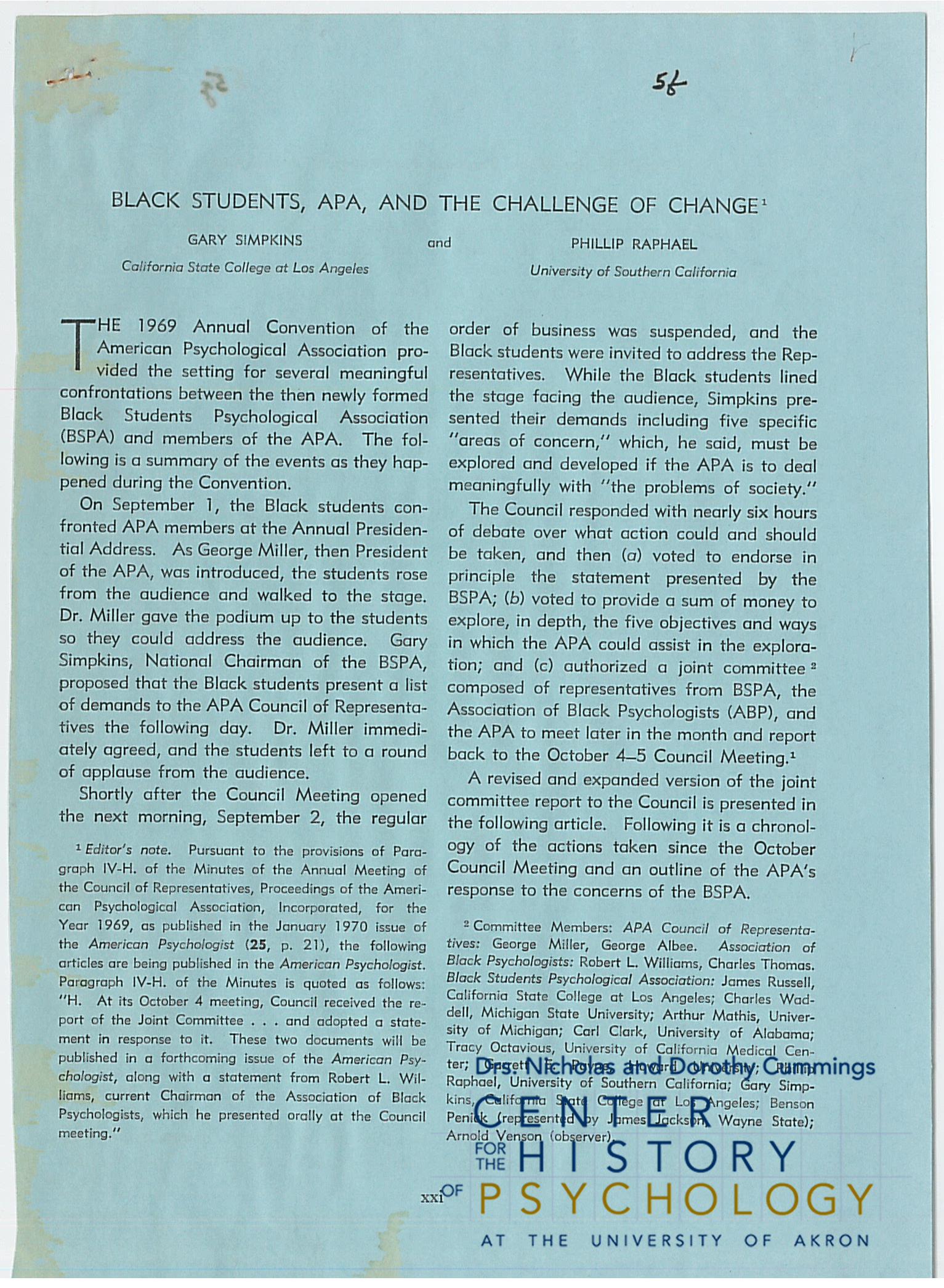

As discussed in the CCHP’s recent video, Robert V. Guthrie and the Search for Psychology’s Hidden Figures, little work had been done prior to the 1970s to seriously spotlight the scientific contributions of Black psychologists in the United States. In the 1950s, Black psychologists remained marginalized in a field that had historically contributed to their societal oppression. Yet circumstances leading up the 1957 Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association led to a purposeful effort among APA leadership to solicit the opinions of the organization’s Black members. In doing so, they collected valuable documentary evidence of marginalization in the nation’s top professional psychological organization.

Backing up for a moment, the situation surrounding the 1957 APA Convention began seven years earlier, in 1950, when the APA resolved that its meetings would henceforth be held only in institutions, hotels, and establishments which did not discriminate on the basis of race or religion. Two years later, following instances of racial discrimination during the 1952 Convention in Washington, D.C., the APA passed an additional resolution vowing not to return the convention to Washington “until additional progress has been made towards democratic treatment of minority groups.”

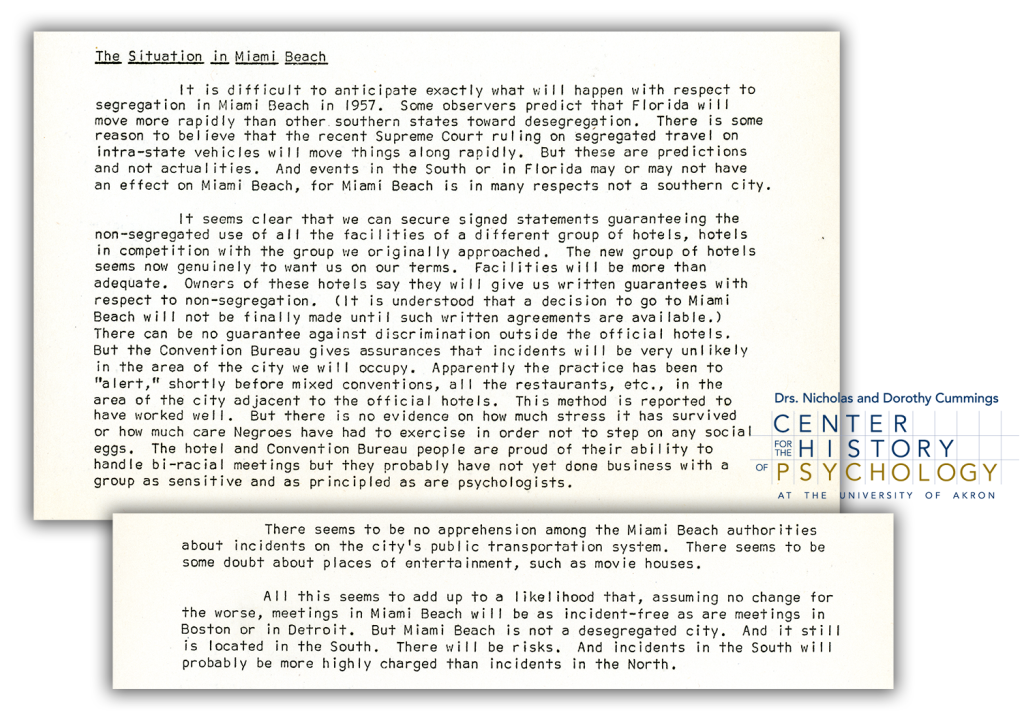

Fast forward to 1954, and the APA’s Council of Representatives had just voted to hold the 1957 Convention in Miami Beach, Florida—a segregated city in an extremely segregated state. APA Executive Secretary Fillmore H. Sanford explained the situation in Miami Beach somewhat optimistically:

(Click each document to enlarge.)

Note the phrase, “these are predictions and not actualities.” No one at APA could know exactly what might happen if they were to host an integrated convention in Florida. The events in Washington, D.C. had shown that, despite assurances from hotels and other establishments, racist harassment and violence remained likely in any highly segregated city.

In the years leading up to the convention, votes were held and public comments were solicited from APA members, depicting a wide range of opinions. The arguments in favor of hosting the convention in Miami Beach did not dismiss the racial segregation of the city and state. Rather, proponents believed that hosting an integrated convention in the South would actually help to advance democracy in the region. As argued by Convention Manager Jack A. Kapchan:

Kapchan’s letter was circulated among APA membership, and his argument gained the enthusiastic backing of many who cited it in their own comments. Votes were cast indicating strong support for holding the convention in Miami Beach.

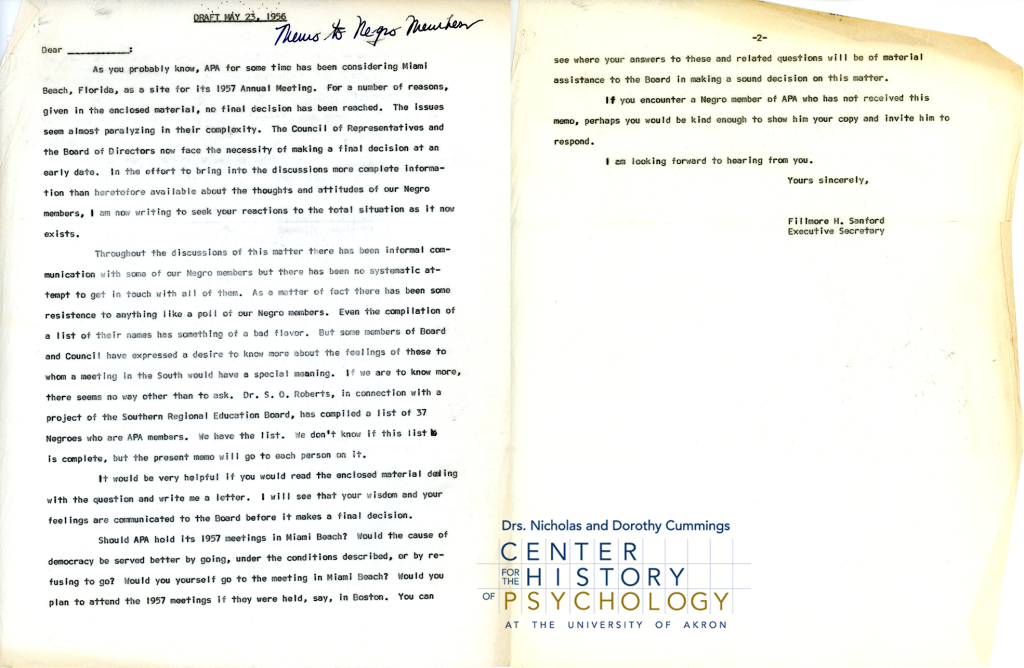

Five days after Kapchan wrote his letter, Sanford drafted a written request to be sent to 37 Black psychologists who were APA members. It read:

Should APA hold its 1957 meetings in Miami Beach? Would the cause of democracy be served better by going, under the conditions described, or by refusing to go? Would you yourself go to the meeting in Miami Beach? Would you plan to attend the 1957 meetings if they were held, say, in Boston. You can see where answers to these and related questions will be of material assistance to the Board in making a sound decision on this matter.

The responses that Sanford received came from a who’s who of notable Black psychologists, some of whom would later be profiled by Robert V. Guthrie in his landmark book Even the Rat Was White. James A. Bayton, for instance, characterized a Miami Beach convention as “a mighty big risk”:

Herman G. Canady, who notably studied racial bias in IQ testing, offered a longer response, holding the APA accountable to its 1950 and 1952 resolutions and placing the situation within a larger social and historical context:

Like Canady, Roger K. Williams offered an important justification for his refusal to attend a Miami Beach convention: the danger of interstate travel.

Williams’s point is an important one. To reach Miami Beach by driving, members would have to pass through the heart of the Deep South, states like Alabama and Georgia where white supremacy, segregation, and anti-Black violence were legally enshrined. This was the era of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a travel guide which identified the all-too-rare hotels, restaurants, and other businesses where African Americans could safely stop during their travels cross-country. Even with the Green Book in hand, Black travelers still put themselves in immense danger travelling through unknown towns and cities in the Deep South.

Not all respondents to Sanford’s letter were opposed to a Miami Beach convention, however. Martin D. Jenkins supported the location, so long as the APA held true to the principles of its 1950 and 1952 resolutions:

Howard E. Wright agreed with Kapchan’s letter in his response, citing a Miami Beach convention as a “desirable social strategy”:

Yet perhaps the most stirring response to this matter came from Mary A. Morton:

You state in your letter that “The issues are almost paralyzing in their complexity.” For me, as an individual, the issues are simple: (1) Will Mary Morton feel secure in joining in any and all proposals for joint activity or will she have to wonder if the particular place involved will welcome her along with all others in the group? … If she is going to have to be concerned about things like these, she stays at home. … Conventions should be intellectually stimulating but they should also be relatively carefree.

… Miami Beach may really become an oasis in a desolate region for purposes of the 1957 meeting, but my acute awareness of how desolate is the region would prevent my enjoying any sojourn into the oasis. Local newspapers and radios would certainly be constant reminders that I was in hostile territory.

In her response, Morton clearly addressed the privilege of both Sanford and the APA’s Council of Representatives. They could easily distance themselves from the dangers of a segregated city, focusing largely upon high-minded principles and potential ideological victories. For Black psychologists like Morton, attending a Miami Beach convention meant putting themselves in “hostile territory,” risking their safety and the safety of their loved ones for the sake of a convention that could just as easily be held in a Northern city.

In June of 1956, a committee of four was assigned to visit Miami Beach to gather further information. Stuart W. Cook represented APA’s Board of Directors and chaired the committee, and was joined by psychologists Robert Kleemeier, Arthur Combs, and S. O. Roberts. Roberts had already voiced his opposition to a Miami Beach convention in no uncertain terms:

The committee carried out a review of dining facilities, hotels, recreational facilities, and transportation. They met with representatives from other organizations, including the American Library Association, who hosted integrated meetings in Miami Beach. In his final report, approved by the rest of the committee, Cook testified that the group encountered no instance of discriminatory behavior. Yet the group could not eliminate all possibility of discrimination, nor could they deny that many Black attendees would feel uncomfortable staying in Miami Beach due to the culture of the South. Cook concluded:

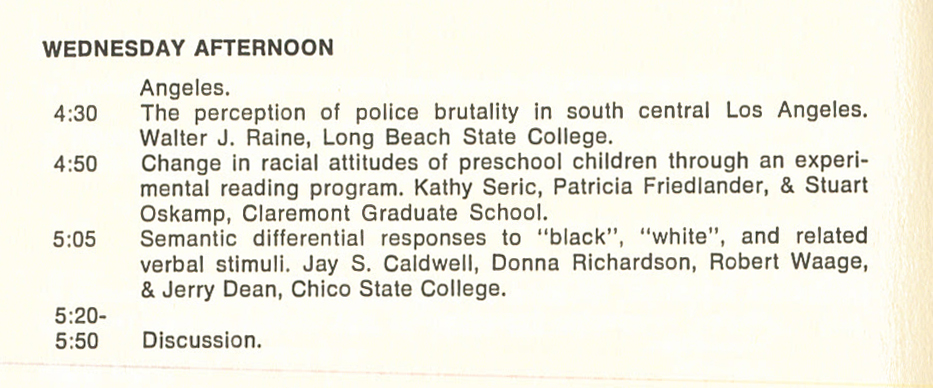

The 1957 Annual Convention of the APA was held in New York City from August 30th to September 5th. The convention would not be held in Miami Beach until 1970, six years after the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally prohibited discrimination on the basis of race.

The prolonged nature of this controversy and the responses of Black members of the APA highlight the tangible ways that marginalization can occur in psychology and other professional fields. In pushing for a Miami Beach convention as part of a “social strategy,” supporters of the location were not entirely misguided. All major civil rights movements in the United States have required their participants to assume some risk of personal harm. Yet it was largely white psychologists who concocted this social strategy, not the Black men and women who were asked to put themselves in harm’s way. Further, most of those Black psychologists were not seeking to take part in an act of defiance against Southern racism—rather, they were simply trying to participate in their professional community and attend a conference for the benefit of their careers and their field.

Had the 1957 APA Conference been held in Miami Beach, Black psychologists who rightly feared for their safety in the South would have been denied access to the largest psychological conference in the United States. The comments of these psychologists helped push the APA to remain true to the principles of racial equality and integration, yet the resolutions of 1950 and 1952 should have invalidated this controversy from the beginning. Circumstances such as these were far from the only systematic barriers faced by Black psychologists in the mid-20th century, but they clearly illustrate how well-meaning policies and resolutions could, and still do, overlook the complexities of racial injustice.

Additional materials on the 1957 APA Convention are available for research in the Stuart Cook papers at the Archives of the History of American Psychology at the Cummings Center for the History of Psychology. To request additional materials from these papers, please contact ahap@uakron.edu.