– contributed by Samantha Hurst, Kent State University graduate student in the Master of Library and Information Science program.

This spring semester, I was fortunate to be able to intern for CCHP. I had the opportunity to work on a variety of digital projects that I was able to contribute to from home. One of these was creating metadata for pieces in the David P. Campbell Postcard Collection. I got to work on the cards in the category “Interesting Messages, Handwriting” which feature cards with handwritten messages on the back that the original collector, Dr. Campbell, found unique. While pouring over these cards and trying to decipher every scrawled cursive letter, I found myself getting lost in their messages, in the wording and other ways in which people chose to express themselves within the confines of a 3×5-inch piece of paper, as well as the imagined meanings in between the lines, the words left unsaid. A few in particular stood out to me:

One card from 1958 carries a message written in a spiral instead of from left to right. The words look like a vortex swirling in on itself, with the text reading “Phil, this is how things have been going the past two days.” The author seems to be alluding to the feeling of being in New York City, which she describes as being nothing like the tranquil scene of Central Park depicted on the front of the card.

One card written in 1978 feels like it was taken from the middle of an argument, with the writer, Sue saying: “It isn’t I don’t have the time. I just don’t think that I have the mental ability to make decisions.” She goes on to talk about her husband falling and hurting his back in the bath tub the day before, but somehow I feel like her husband’s back is the least of Sue’s problems.

Another card, written in 1917, during the height of World War One, is written by a young man to his uncle, telling him that he’s joined the Navy, saying “[I] like it fine. I eat on the ground and do my own washing. It is a new experience.” A synopsis of Navy life during that period that I have to imagine is leaving out some less savory details.

One of my favorite postcards might be the one that I found the most confounding. A card in which the message on the back simply reads “nothing at all to say” signed “PAT.” A message carrying virtually no meaning to anyone other than perhaps Clarence Korn, who received the card in January of 1915.

Written on a simple black and white card, the front image depicting a cartoon of a child writing a post card and a short poem expressing the feeling of wanting to send a postcard to a friend when a letter isn’t necessary. Virtually everything about this postcard feels completely superfluous in a way that genuinely took me aback when I first saw it. Pat seems to have just sent Clarence a postcard about writing a postcard with no other message beyond “here is a postcard.” Was there some secret meaning to this act? Was there a private joke between the two of them? Was this card in response to something Clarence said or did to Pat? It reminded me of the act of sending a friend a random picture with no explanation, or even the now seemingly ancient Facebook “poke” function, designed to get your friend’s attention for no specific reason. All just random acts that say “I may not have anything to say, but I still want you to know I’m here.”

These postcards are so fascinating to me because they are essentially just pieces of paper, designed for advertising more than anything else, but they have the power to contain such heavy sentiment in such a small space. Although the full contexts of all of these messages have been lost to history, the feelings that they evoke are extremely familiar. We often think of people from the past as being very different from us, but if nothing else, the David P. Campbell Postcard Collection can teach us that in some ways, people never seem to change. The way we talk to friends and family can often be humorous or contentious. We often leave out the more painful details in order to spare someone’s feelings, or keep loved ones from worrying. We often don’t have anything particularly important to say, but want to keep in touch with people anyway, just for the sake of it.

The three boxes of spools in the AHAP collection

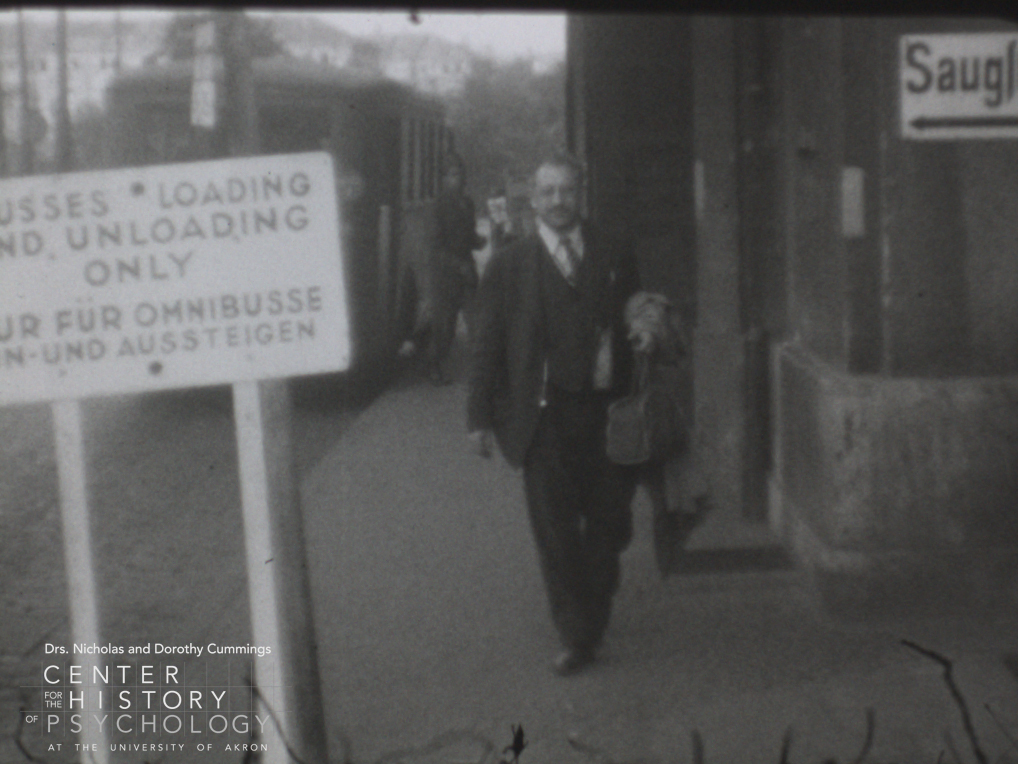

The three boxes of spools in the AHAP collection From a 16mm film of Boder in Germany

From a 16mm film of Boder in Germany