– contributed by Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr.

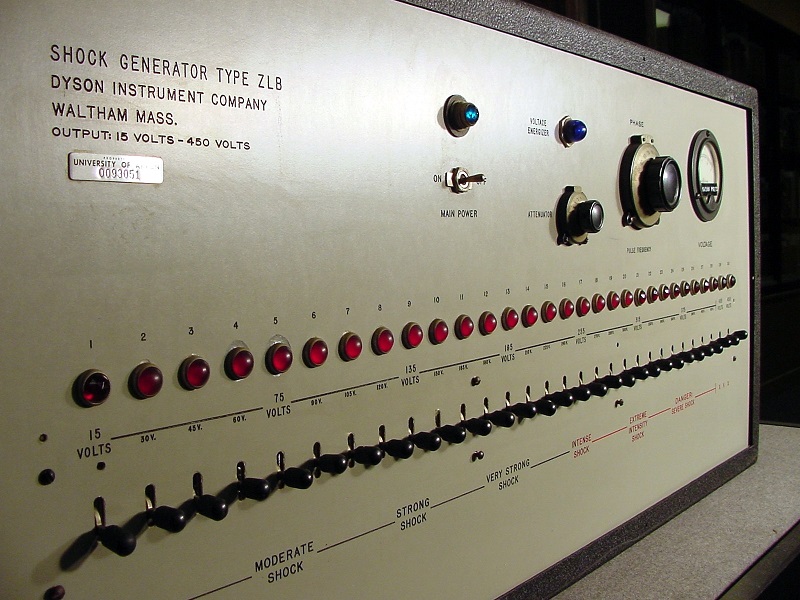

The collections of the Cummings Center for the History of Psychology are rich with treasures that tell the history of psychology over its roughly 150 years of existence as a science. One part of the collection contains rare and sometimes unique artifacts and scientific instruments, more than 1,000 of them. They span the history of psychology. Some pieces in the collection are more recent such as a B. F. Skinner aircrib from the 1940s-1950s designed to improve infant care and Stanley Milgram’s faux shock box from his famous studies on obedience to authority in the 1960s. These pieces of apparatus are quite large. But some of the treasures in the Center’s collection can fit in your hand, and a few are meant to do just that.

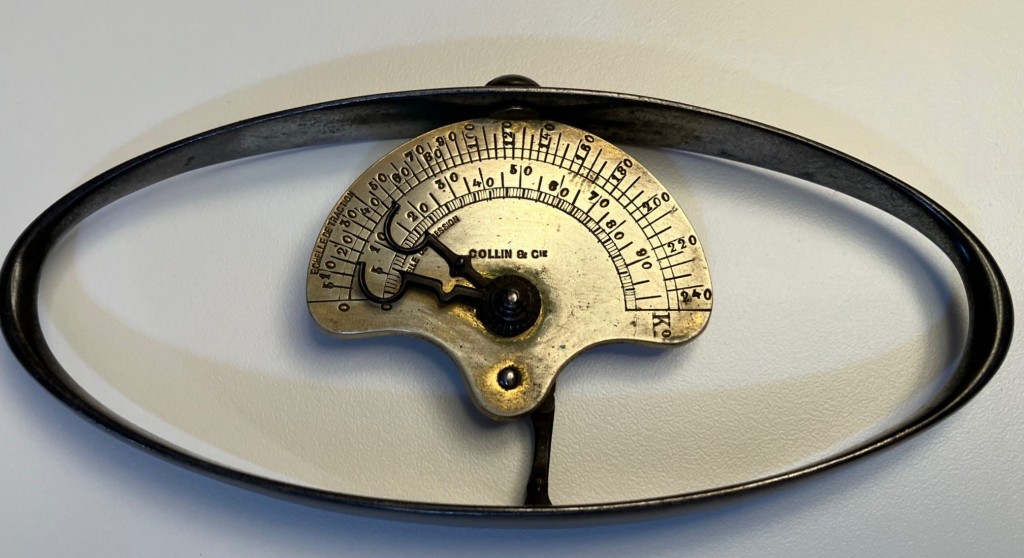

Consider the item below, which is one of the Cummings Center’s latest acquisitions. The ellipse, which is made of steel, measures 5 inches by 2 inches. And in the middle of the ellipse is a brass plate that has been silvered, with two movable “hands” that are used to mark the numerical readings on the plate. What is it? A hint: it was meant to fit in your hand.

In fact, this instrument was one of the earliest to be used in psychological research in the late 1800s. There were 40 psychology laboratories in existence in the United States by 1900 and most of them would have had this device or a similar one in their collection of apparatus. What purpose did it serve in psychological research? We will answer that question in a moment.

This object is a hand dynamometer, a device engineered to measure the strength of one’s grip. The dynamometer pictured above was the most popular instrument in its day, designed around 1867 by Anatole Collin (1831-1923), a French engineer known for the development of surgical instruments. You can see his name on the brass plate. The device above would be held in the palm with the long axis of the ellipse laid across the palm. The hands of the device would be set at zero and then the person would be told to squeeze as hard as possible by making a fist and exerting as much pressure as possible on the two long sides of the ellipse. Measures might be taken of grip strength in each hand. And several measures might be taken of each hand to get a more reliable result.

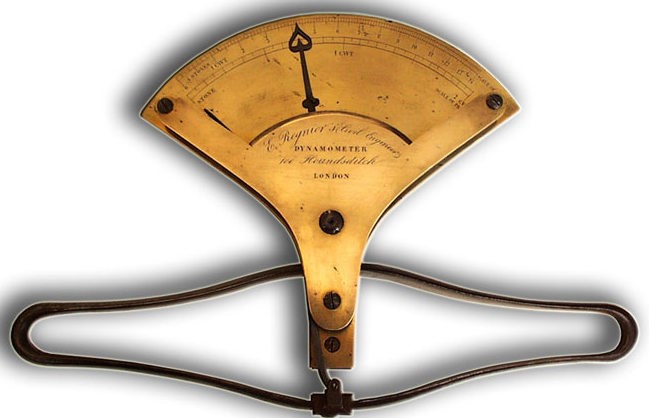

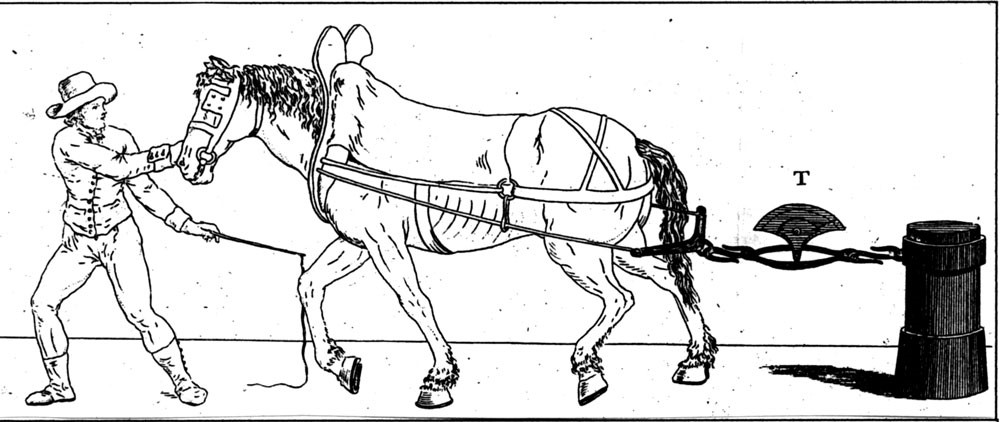

The dynamometer was invented by a French engineer, Edme Régnier (1751-1825) in 1798. It was used to test muscular strength in both humans and other animals, particularly horses. Régnier was an inventor working principally in the design of firearms. One of the earliest uses of the dynamometer was to measure the pulling strength of horses used by the military in transporting artillery such as cannons (see figure below). Clearly the dynamometers used in these instances were not hand dynamometers.

But Régnier had invented that as well. Among its earliest uses was the measurement of grip strength in different races by ethnologists. Below is the Régnier hand dynamometer which measured grip strength in both hands simultaneously.

So why was this instrument of interest to the early psychologists? Nineteenth-century physiologists and anthropologists believed that chief among human evolutionary achievements was the development of the hand and fingers, and that the control and utility of these movements was related to intelligence. Sir Francis Galton, an English polymath and half cousin of Charles Darwin, was using the hand dynamometer in the late 1880s as part of a testing program of human cognitive, sensory, and motor abilities, a program of measurement he labeled anthropometry. Below is an example of the individual records that Galton obtained from each subject who was tested in his Anthropometric Laboratory in London. This record is dated August 11, 1888 and the subject was a 28-year old psychologist, James McKeen Cattell, who would later establish the psychology laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University. You can see that “Strength of squeeze” was greater in his right hand (89 pounds) than his left hand (82 pounds).

Cattell was strongly influenced by Galton’s work and included some of Galton’s measures in the mental testing program that he developed in the United States in 1890. Cattell focused more on sensory and cognitive measures than Galton but one of the tests that he included among the ten comprising his test battery was a test of grip strength using the hand dynamometer. In fact, it was the first test listed in his battery. Cattell described why this test was important: “The greatest possible squeeze of the hand may be thought by many to be a purely physiological quantity. It is, however, impossible to separate bodily from mental energy. The ‘sense of effort’ and the effects of volition on the body are among the questions most discussed in psychology and even in metaphysics.”

We do not know what dynamometer Cattell used in his work but a most likely candidate would be the Collin hand dynamometer pictured at the beginning of this blog. In their excellent article on the history of the hand dynamometer, Serge Nicolas and Dalibor Voboril (2017, L’Année Psychologique, 117, 173-219) wrote:

…the instrument that was to become most firmly established was the one made by Collin and used, in particular, in the experimental work of [Alfred] Binet and other psychologists of renown. This instrument was to become an indispensable tool not only for psychologists but also for physicians, physiologists, anthropologists and medical doctors within the context of their work … The various lists of equipment available in the psychology laboratories [in the 1890s and early 1900s] … always have dynamometers close to the top, and in particular the Collin dynamometer. It enjoyed global success…

The hand dynamometer has continued to be used in a variety of fields since its inception and remains a popular scientific and medical instrument today. Many modern versions resemble the model shown below, manufactured by the Charles Stoelting Company of Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s. This instrument is also in the apparatus collections of the Cummings Center.

Today, one of the principal uses of this instrument is to understand the relationship between mental and physical processes in aging. Pictured below are two current devices that can be purchased online or from medical suppliers. The one on the left sells for about $20. The one on the right purports greater precision and is sold for psychological, physiological, and medical purposes. It’s price is around $250.

But if you long for the ways things used to be, you can still purchase a brand new Collin Dynamometer in 2024 from GerMedUSA, a surgical instruments company in Garden City Park, NY. They manufacture one for children and one for adults and they sell for around $240. Here is the image from their catalog. It is doubtful that Mr. Collin ever imagined that the device he developed in 1867 would still be manufactured in virtually identical form 157 years later!

There are multiple reasons why these devices continue to be used. For example, they are used in rehabilitation programs for individuals suffering hand injuries to measure recovery of function. Another very important use of the device is to study changes in grip strength in human aging. There are more than 50 articles published in the last ten years that support the value of testing grip strength as a window into understanding cognitive decline in aging, especially forms of dementia.

It isn’t just about horsepower anymore.