Contributed by Rhonda Rinehart.

Chances are if you had a question, Little Blue Books had an answer. Actually, many answers. On any topic. For everyone, everywhere. Little Blue Books were your local library. They were the 1920s version of Wikipedia. And they kept the post office in business. At 5-10 cents a pop, Little Blue Books weren’t free but they were cheap, and they could be shipped to any address in the world for nothing. Always 3 ½” x 5 ½”, these tiny tomes of paper and staples were easily transportable, whether you were delivering them or reading them.

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius hoped to find a place, even if a small one, in the annals of literary history. More specifically (and more colorfully), he said this:

At the close of the 20th Century some flea-bitten,

sun-bleached, fly-specked, rat-gnawed,

dandruff- sprinkled professor of literature

is going to write a five-volume history of the books

of our century. In it a chapter will be devoted to

publishers and editors of books, and in that chapter

perhaps a footnote will be given to me.

With apologies to professors of literature, Haldeman-Julius did indeed carve out a place of his own among the publishing world. What was once an earnest (and successful) endeavor to provide affordable and accessible reading to the entire world population (for real!) has now become a collector’s delight.

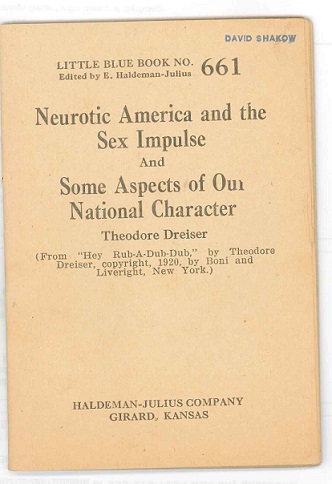

In the areas of psychology, psychiatry and self-help, Little Blue Books offered a surprisingly large selection of titles that ranged from topics like autosuggestion to testing to animal behavior. Fairly cutting-edge stuff for the general public of the early 20th century.

The small collection of 34 Little Blue Books donated to the Center by Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr., contains several titles on psychoanalysis in the ever-popular “know thyself” format. Courtesy of the Haldeman-Julius publishing company, you can learn how to psychoanalyze yourself, and you can read along as a popular author psychoanalyzes himself and the entire United States.

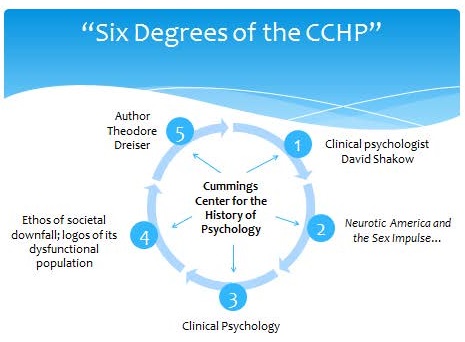

But what’s even more fun than psychoanalyzing yourself (at least for this archivist) is making a connection from something as broad and far-reaching as the nearly two thousand Little Blue Books titles to something very specific located right here in the archives at the Cummings Center.

New Experiments in Animal Psychology (Little Blue Book No. 693) features work from all the well-worn and heavy-hitting names of those early pioneers of animal psychology – Thorndike, Yerkes, Watson, Witmer – and then suddenly hits the reader with an illustration on page 19 (something quite rare in Little Blue Books) – a depiction of Ivan Pavlov’s famed drooling dog experiment, demonstrating classical conditioning.

Illustration in Little Blue Book No. 693 of Pavlov’s Conditioned Reflex Apparatus monitoring animal responses to stimuli

Now comes the good part. The Center’s collection of objects and artifacts has a very small replica of the set-up that Pavlov used in his experiments to measure a dog’s salivary response to certain stimuli like food or later, the sound of a metronome or a buzzer. Like a miniature laboratory, this cute and portable likeness of the real thing was used for teaching about those conditioned responses without the mess of a drooling dog in the classroom.

And that’s what is so fun about working, studying, and researching here at the Center. There are those moments that happen when a connection is made and you light up and say, “Yes! I’ve seen that before” or “This was on TV last night!” Even if you don’t have a background in psychology (I’m raising my hand here), there are so many objects, so much media, and mountains of written and published works that relate to everyday life to be found at the Center – you will not only be able to psychoanalyze yourself, you’ll be able to recognize the science behind a drooling dog.

Search the finding aid for more information. Please contact us to view these Little Blue Books.