– contributed by Tony Pankuch.

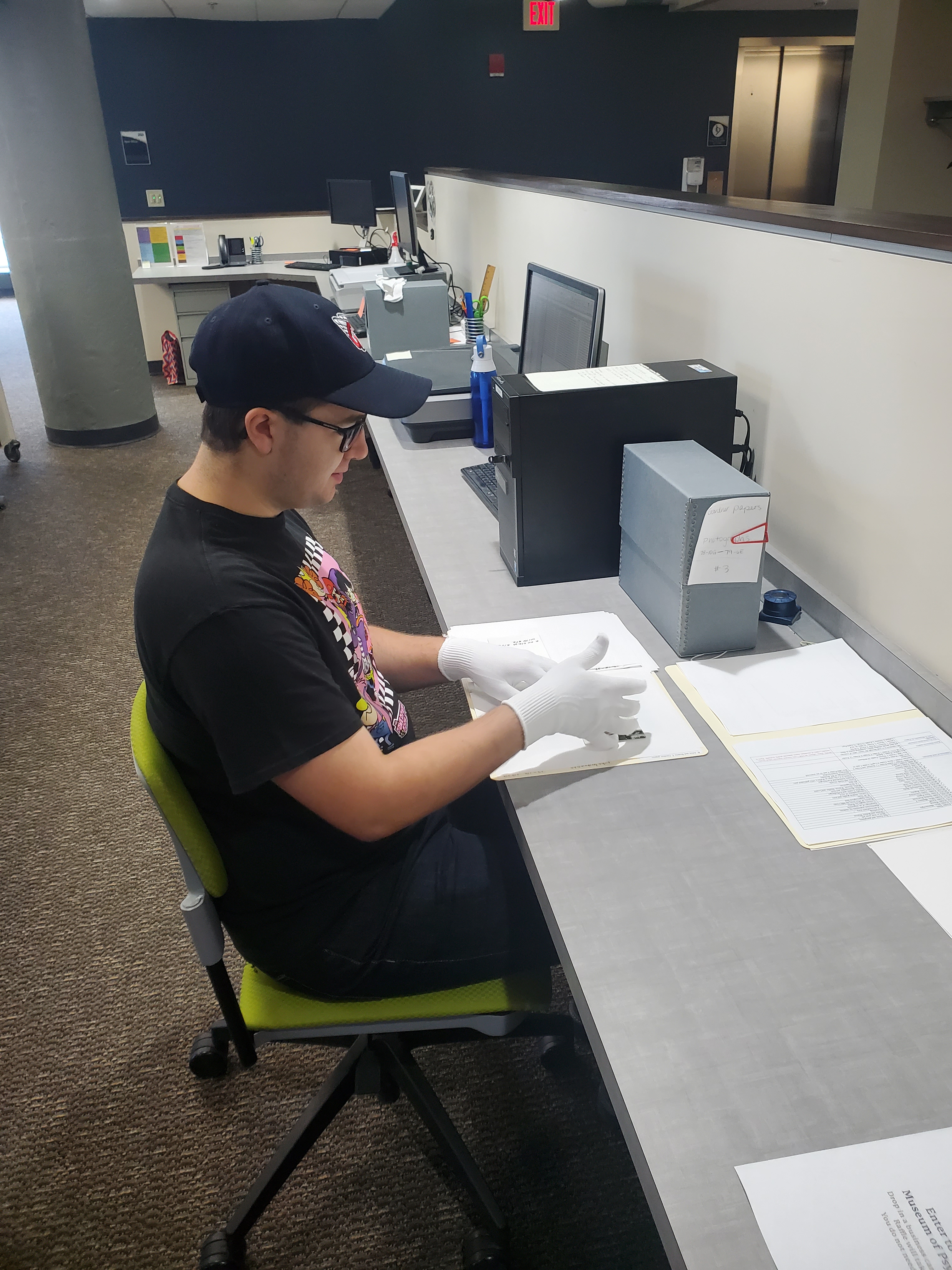

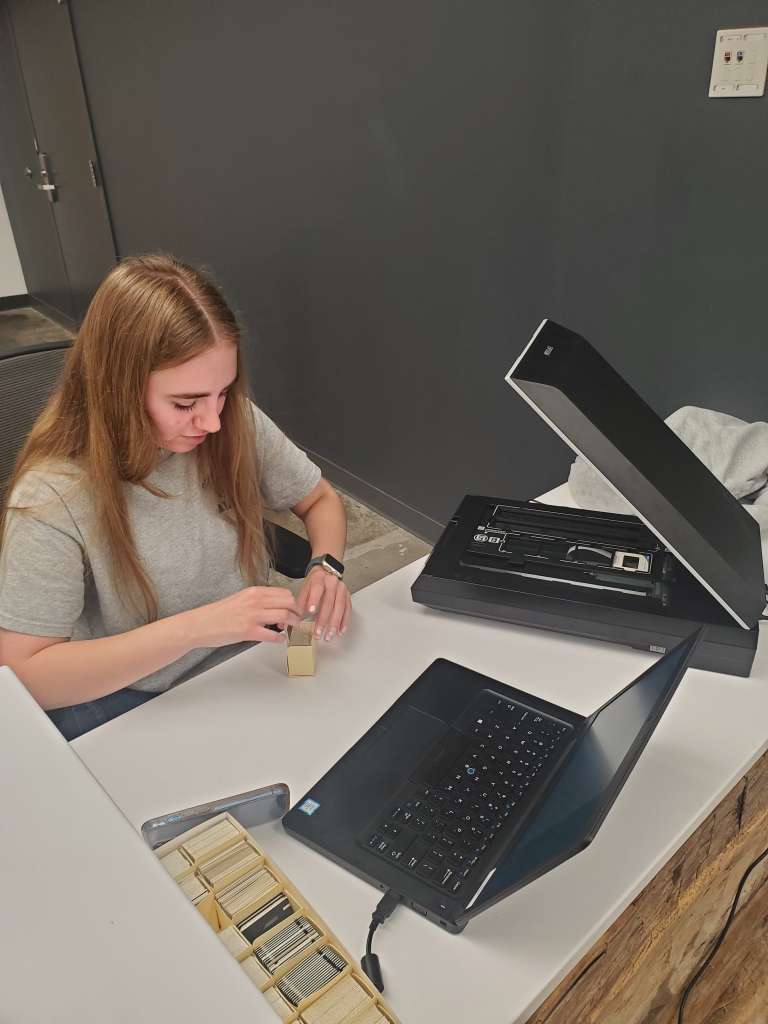

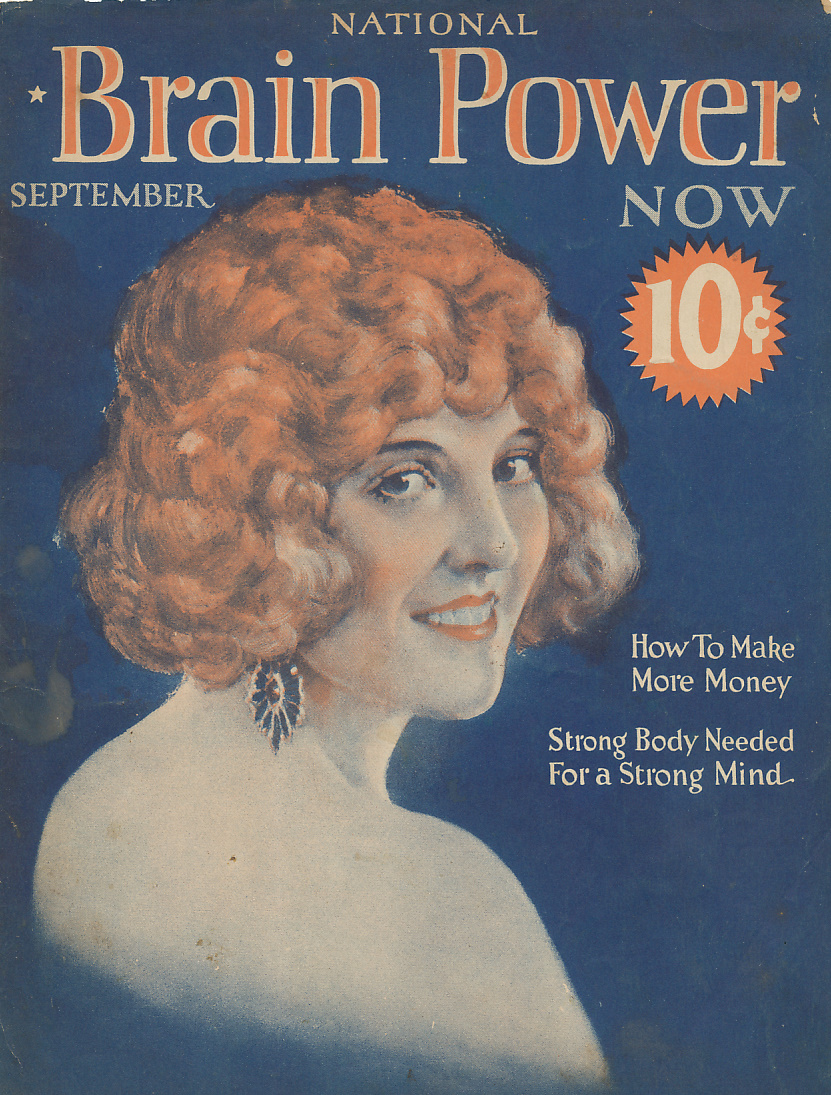

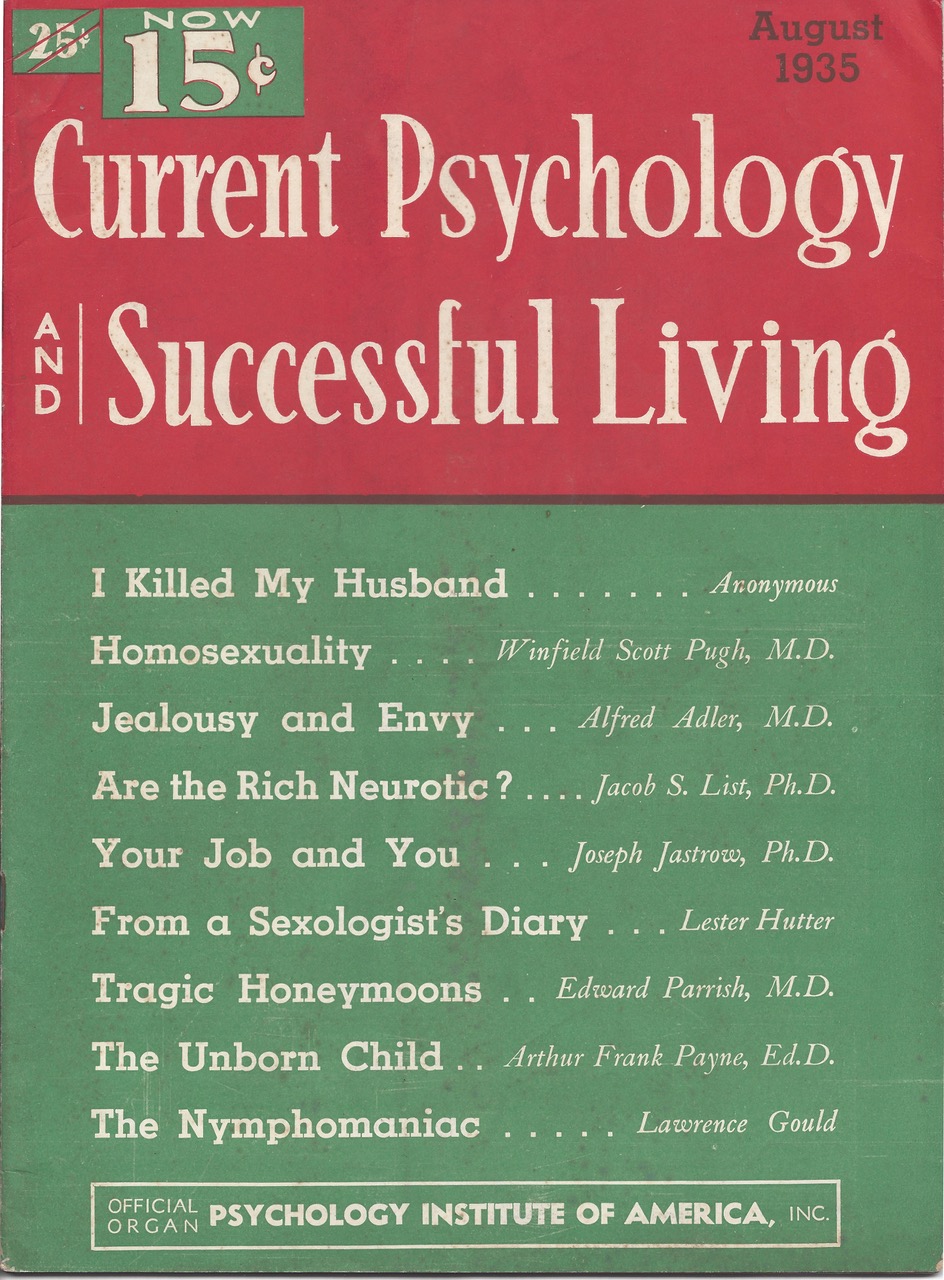

Next week, the Cummings Center will launch its newest exhibit, Sexology: Science & Sensationalism, which explores the 50-year run of Sexology magazine (1933-1983), a sex science publication sold to popular audiences as “The Door to Sex Enlightenment.” I’ve had the pleasure of helping to supervise our current cohort of Museums & Archives Studies Certificate students in researching, curating, and designing this exhibit, and along the way I’ve been fascinated by Sexology’s contents—a unique blend of science, opinion, advice columns, and tabloid fodder.

Sexology’s contributors came from a wide variety of backgrounds and included some genuine icons in the history of sex science – folks like Harry Benjamin, a pioneer in gender-affirming care for transgender people, and Wardell B. Pomeroy, who co-authored the famous “Kinsey Reports” with Alfred Kinsey and Clyde Martin. But for every recognizable author, there are numerous others whose contributions have attracted little historical attention. This blog is the first in a series spotlighting Sexology’s lesser known (but equally interesting) contributors.

Grace Verne Silver (1889-1972) was among Sexology’s earliest authors, writing numerous articles for the magazine throughout the late 1930s. Since its inception, the magazine had placed a focus on the issue of sex education, generally arguing in favor of honest, open discourse about sex and sexuality. Through her contributions, Silver helped to bolster this argument. Take, for example, her 1937 piece, “Sex Ignorance Is Criminal.”

“Knowledge gives happiness as well as power; nothing but misery ever grows out of ignorance. This is as true of marital relations as in any other human affairs. Women need knowledge even more than do men. In the first place, men get knowledge—of sorts; in the second place, women pay higher for their mistakes and suffer more from their own ignorance than do men. As to what women have suffered because of man’s ignorance—in addition to their own—that is beyond any computation!” – Grace Verne Silver, Sexology 5(1), September 1937.

In the above article, Silver emphasized the importance of sex education for young women, writing that “much suffering could be prevented if women were told a few simple things before their marriage.” This interest in the wellbeing of women (and the harms inflicted upon them by men) was a hallmark of Silver’s writing for Sexology.

“Marriage is not the proof of man’s love, but the proof of his desire for exclusive ownership, and may or may not have anything to do with love. Usually it also proves he wants a housekeeper and nurse. Women know that the ‘security’ offered by marriage has been much overestimated.” – Grace Verne Silver, Sexology 4(9), May 1937

Silver’s contributions to Sexology were only a minor piece of her overall legacy, however. In addition to advocating for sex education and feminist causes, Silver was a prominent socialist and labor activist who lectured around the United States. According to her daughter, she opened the first socialist bookstore in Los Angeles, which was raided three times by members of the American Legion. She was once arrested on charges of assault and battery after a fight broke out during one of her speeches. Her occupation—openly listed as “Socialist Lecturer” on her daughter’s birth certificate—was a dangerous line of work during the Red Scare of the late 1910s.

Despite her contentious views, Silver established a positive working relationship with Sexology’s first editor, David H. Keller. Keller edited several magazines at this time, and Silver’s contributions were featured regularly throughout his publications. In 1937, Silver’s writing appeared in all 12 monthly issues of Sexology.

“There is a theory that a girl’s husband should be her instructor. How shall he teach what he does not know? Men, as a class, know even less about the intimate life of women than women know. Men have learned much that is not true, much they need to forget when they marry.” – Grace Verne Silver, Sexology 5(2), October 1937

Silver’s views occasionally contradicted those of her editor. Her 1938 article “Normalcy of Petting” was prefaced by a note from Keller, which cautioned readers that “the Editor must express disagreement with many of the writer’s opinions, although full approval of the concluding paragraph.” In this article, Silver defended the practice of “petting” between young men and women, once again adopting a feminist perspective on the subject. “Personally,” she wrote, “I’d rather see a girl discover a man to be a cad before she married him, than have her wait to learn it later.”

“When young people indulge in experimental petting, one of two things must happen sooner or later: they will find they have made a mistake, that they do not care enough for each other to risk marriage, and ‘call it off’; or they will find their love intensified, their longing to be together will overwhelm them, and they will want to marry.” – Grace Verne Silver, Sexology 5(8), April 1938

Though Silver’s contributions to Sexology appear to have ceased in the early 1940s, her writings undoubtedly helped the magazine to establish a voice in its early years. Sexology, at its founding, was a fairly radical publication, inciting controversy as it brought taboo subjects to popular audiences. It’s not surprising that a lifelong activist well-versed in political censorship would be among the magazine’s earliest contributors.

Silver’s legacy has lived on partly due to her daughter, Queen Silver. Queen followed in her mother’s footsteps and began lecturing publicly at just eight years old. She was a vocal atheist, socialist, and feminist whose young activism reportedly inspired Cecille B. DeMille’s 1928 feature film The Godless Girl. Queen’s free-spirited nature likely owes a lot to her mother, whose Sexology articles consistently defended women’s rights and the bold new ideas of the “modern youth.”

“Twenty-seven years ago, I elected to become a free and single mother. Neither I, nor my now fairly successful grown daughter, have ever had reason to regret the step. Starvation at times; hard work at other times; some minor criticisms in the early years, when there were fewer ‘moderns’ than nowadays. Under similar conditions, I would repeat the venture; I hope my daughter would have courage to do likewise.” – Grace Verne Silver, Sexology 5(4), December 1937.

The papers of both Grace Verne Silver and Queen Silver are held by the Duke University Libraries in Durham, North Carolina and are open for research. But if you’d like to explore Grace Verne Silver’s contributions to Sexology magazine right here in Akron, Ohio, drop by the Sexology: Science & Sensationalism exhibit, opening May 2. We’ll be featuring three of her articles among the 80+ issues of Sexology magazine on display.

And keep an eye on our blog in the coming months for more posts about the little-known writers of Sexology magazine!

References

Kirsch, J. (2000, November 1). This Hometown Girl Radical Fought Many a Battle on the Soapbox. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-nov-01-cl-44988-story.html

McElroy, W. (2011). Queen Silver: The Godless Girl. Prometheus Books.

Silver, G. V. (1937, May). Woman’s New Sex Freedom. Sexology, 4(9), 4-7. Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection, Archives of the History of American Psychology, Akron, OH.

Silver, G. V. (1937, September). Sex Ignorance is Criminal. Sexology, 5(1), 4-7. Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection, Archives of the History of American Psychology, Akron, OH.

Silver, G. V. (1937, October). Sex Ignorance is Criminal (Part Two). Sexology, 5(2), 4-7. Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection, Archives of the History of American Psychology, Akron, OH.

Silver, G. V. (1937, December). Motherhood Without Marriage? (Part Two). Sexology, 5(4), 4-7. Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection, Archives of the History of American Psychology, Akron, OH.

Silver, G. V. (1938, April). Normalcy of Petting. Sexology, 5(8), 496-500. Ludy T. Benjamin, Jr. Popular Psychology Magazine Collection, Archives of the History of American Psychology, Akron, OH